This narrative was written as if Robert “Big Bob” Ealy was telling his story himself. It was read on the buses during our Birthplace Tour to Nash County, North Carolina on July 20, 2024.

Hello, My Descendants! Today is the day. I got a lot to tell y’all. Y’all have this handout to read because a lot happened during my younger years here in North Carolina.

I see that y’all are headed out to Nash County to see where I originally came from. My heart is so full watching this unfold. But let me tell y’all about my beginnings.

My official name is Robert, but as y’all know, people called me Big Bob. Although I lived most of my life in Leake County, Mississippi, I was born into slavery here in North Carolina, without realizing what all laid ahead of me. But my Momma was aware that life would be changing for us. Her name was Annie. We, as enslaved people, had no control at all of our own lives. That’s why I was taken away from here when I was around 16 years old.

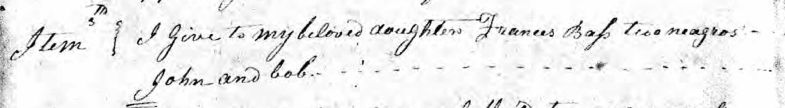

In 1822, my ole Masser died. His name was Jesse Bass. I don’t remember him very well because I was so young, maybe about 3 years old. He wrote a will before he died, and he gave me and my brother John to his youngest daughter, Miss Fanny Jane.

When Masser Jesse Bass died, little Miss Fanny Jane was considered an orphan in the eyes of the court, even though her mother was still alive. White women had no rights either, but they weren’t considered property like cattle and hogs like we were. The Nash County court appointed Masser Jesse Bass’s son Isaac as young Miss Fanny Jane’s legal guardian. Isaac had to manage her property. So, my brother John and I were able to remain there on the Bass place with Momma and my grandmother Pheby.

You see, Momma remained the legal property of Jesse Bass’s wife Ms. Frances because her daddy Ben Pearce had given Momma to her. A year after Masser Jesse died, Ms. Frances remarried to William Hunt in Sept. 1823. But he had no legal rights to me and John. We legally belonged to little Miss Fanny Jane.

Trouble brewed between Ms. Frances and William Hunt. You see, a day before she married William Hunt, she secretly went to Nashville, the county seat of Nash County, and filed a deed of gift at the courthouse giving Momma, my infant brother Lazarus, and Uncle Ned to Miss Fanny Jane and Little Coffield Bass after her death. Y’all gonna see Nashville and the courthouse today. They were the two kids that Ms. Frances had with Masser Jesse Bass. She did not tell Hunt what she had done. She was a sneaky white woman, but she wanted to make sure that her property went to her two children. When ole man Hunt learned about it, he was fit to be tied.

Well, Little Coffield Bass died shortly afterwards. Masser Edwin Bass was appointed administrator of Coffield’s estate, and he purchased Momma, Lazarus, and Uncle Ned. Edwin was ole Masser Jesse Bass’s son, too. William Hunt decided to take Edwin to court to gain full ownership of them because he wanted legal rights to sell them to settle debts that Ms. Frances had racked up. The court case lingered in Nashville for nine years. This stressed Momma out so bad because her fate was up in the air. Losing me and my brother John was a real concern. Our lives were always in others’ hands. They could do anything with us as they saw fit. Very very hard times!

In December 1832, the North Carolina Supreme Court finally decided that William Hunt, being Ms. Frances’s new husband, had legal rights to Momma, Lazarus, and Uncle Ned. But he worked out an agreement with Masser Edwin Bass for him to keep them. We were relieved about that because Momma, Lazarus, and Uncle Ned would not be left back in North Carolina with Hunt once we all packed up and headed to Mississippi.

You see, they were all planning to leave North Carolina for Mississippi. I could hear the conversations when I went up to the big house. They all began to sell pieces of old Masser Jesse Bass’s 900 acres that he had left to them. Today, y’all are gonna see where it was located in Nash County.

In about 1835, young Miss Fanny Jane became old enough to marry Masser William Eley. We called him Masser Billy. He was a mean ole white man. When they married, my brother John and I legally became his slaves because women had no rights. But they sold John to Miss Fanny Jane’s half-brother, Jordan Bass, because they needed some money.

So, around 1836, we all made the long journey down to Hinds County, Mississippi, just northwest of Jackson near Pocahontas. It took us a lot of days to get there. I had to get off the wagon and walk sometimes. About 20 of us were on that wagon train. It was a tiresome, long journey from North Carolina to Mississippi.

Masser Billy Eley and Miss Fanny Jane didn’t stay in Hinds County long, about 2 years. He purchased 80 acres of land about 50 miles away, over in Leake County, in 1839. We settled just a mile west of Good Hope, and I lived the rest of my long life in and around Leake County. I heard that Masser Jordan Bass eventually took my brother John to Texas. I never saw him again. This broke my heart and made me so sad.

Now, you are all back to see where I started out. My family’s blood, sweat, and tears are in this North Carolina soil. Generations before me are in this soil. Words can’t express how happy I am that you all chose to come back here to see it and to commemorate my origins. Masser Jesse Bass’s old house and the slave cabins ain’t there anymore, but you will see the area and land where I was born. You can call it Ground Zero – my beginnings.

The research of this history can be read in Ealy Family Heritage: Documenting Our Legacy.

© Written by Melvin J. Collier, 2024. These are factual accounts based on years of research.